Access Management , Application Security & Online Fraud , Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Zoom Fixes Flaw That Could Allow Strangers Into Meetings

Check Point Guessed Valid Meeting IDs, Allowing for Snooping

Zoom Video Communications has fixed a vulnerability that - under certain conditions - could have allowed an uninvited third party to guess a Zoom meeting ID and join a conference call.

The vulnerability was found by Check Point Software Technologies, which published its findings. The attack, however, is no longer possible thanks to Zoom having put mitigations in place.

See Also: Panel Discussion | Securing the Open Door on Your Endpoints

Vulnerabilities in conferencing software are notable because of the pervasiveness of such systems in businesses. Poorly secured systems can give hackers remote access to microphones and video cameras, including in board rooms, resulting in the exposure of sensitive or confidential information.

Zoom says it fixed the flaws found by Check Point in August 2019, and that it has “continued to add additional features and functionalities to further strengthen our platform."

Zoom adds: "We thank the Check Point team for sharing their research and collaborating with us.”

Guessing Meeting IDs

The flaw was due, in part, to an attacker potentially being able to guess a valid Zoom meeting ID, according to Alexander Chailytko, a research and innovation manager at Check Point, who notes that all Zoom meeting IDs have nine to 11 digits.

Knowing the meeting ID is enough to join a call, unless a couple of defenses get enabled. One such defense is requiring participants to enter a password. Another is a feature that allows an administrator to manually approve people who are joining a call.

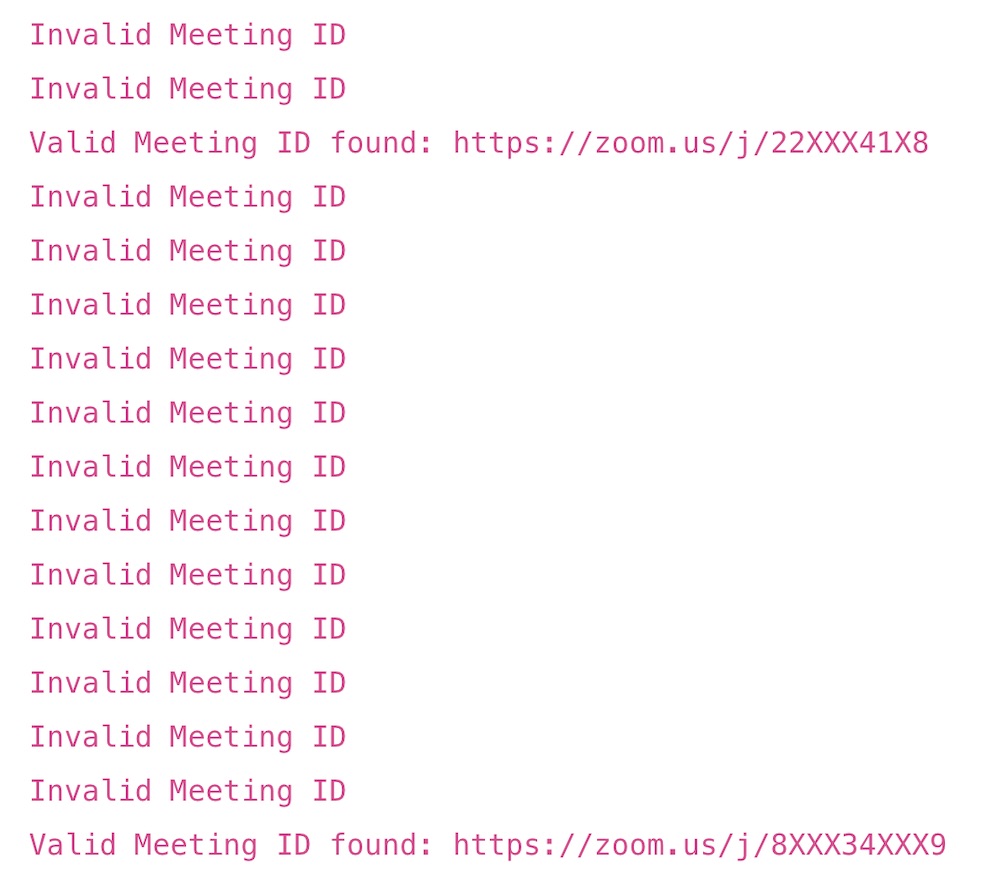

Check Point explored whether it was possible to generate large numbers of valid meeting IDs. Chailytko writes that the researchers created URL strings with possible meeting IDs, and then they were able to check those against Zoom’s systems to figure out which ones were legitimate.

The key was HTML tags within Zoom’s web application, says Omri Herscovici, security research team leader at Check Point.

“We found that when trying to access an invalid meeting ID, a certain HTML tag with a specific name exists, and when the ID was valid that HTML tag was absent,” Herscovici says via email. “So we wrote a small script to get the source code of random Zoom conversation web pages with different meeting IDs, and checked if the tag was present or not. If the tag didn’t exist – we knew the that meeting ID is valid.”

Some of those guesses were correct.

“We were able to predict around 4 percent of randomly generated meeting IDs, which is a very high chance of success, comparing to the pure brute force,” Chailytko writes.

Zoom has addressed the problem in several ways. First, Zoom now makes meetings password-protected by default, Check Point writes. According to guidance issued by Zoom, however, it appears that Zoom administrators can permanently disable that default.

But Zoom users can also add a password to an already scheduled meeting. In addition, account administrators can enforce Zoom meeting passwords at account and group levels.

Part of the problem that allowed Check Point to probe whether a meeting ID was correct is that Zoom’s systems provided either a yes or no response to such queries. After recent changes, however, any attempt to join a specified meeting ID will result in a meeting page loading, whether or not the meeting ID is valid. As a result, “a bad actor will not be able to quickly narrow the pool of meetings to attempt to join,” Check Point writes.

Finally, Zoom says it now watches for devices that appear to be scanning for meeting IDs - for example, as part of an attempted brute-force attack - and will block them.

Zoom didn’t immediately respond to a question from Information Security Media Group about whether a meeting interloper would be known to others in a call. Most conferencing software shows a list of participants, so even if someone unknown joined a call, one of the other participants potentially might notice and query their identity.

Follows Zoom's Mac Software Problems

The meeting invite vulnerability spotted by Check Point isn't the first security problem to have bedeviled Zoom. In July 2019, the company was the focus of an unusual situation that led to Apple forcibly removing the company’s software from users' Macs (see: Apple Issues Silent Update to Remove Old Zoom Software).

Earlier last year, security researcher Jonathan Leitschuh found a bug that could be used to suddenly launch Zoom’s client and force someone to join a conference call - and, depending on how Zoom was configured, add them with their video camera enabled (see: Zoom Reverses Course, Removes Local Web Server).

Leitschuh also found that Zoom installed a local web server that remained behind even if a user uninstalled the application. The web server wasn't scrubbed, in case someone clicked on a Zoom meeting link, so that the app would automatically be reinstalled. But security experts said the local web server was a threat, and further research discovered that it could also be remotely exploited by attackers.

Based on the threat posed by the Zoom web server, and users' inability to remove it, Apple made its unprecedented move to issue an operating system update that forcibly excised the web server from systems.